For S. Maheswari, 45, receiving ₹1,000 a month under the Kalaignar Magalir Urimai Thogai scheme means being able to afford her diabetes medicines. “It’s very difficult to run a family of four with just my monthly earning of ₹10,000. I have to ensure the education of two children, look after my disabled husband, and do the household chores. My health takes a back seat,” says the resident of Mahabalipuram, who runs a tea stall.

The medicines cost about ₹1,500. She started taking the pills only after the scheme was introduced because she finally had enough money to spend on necessities.

Introduced in September 2023, the scheme is aimed at recognising women for doing the domestic work in their household that has historically fallen on the women’s shoulders. The government gives ₹1,000 a month to women heads of families earning less than ₹2.5 lakh a year. With the scheme, Tamil Nadu became the first State in the country to recognise women’s unpaid domestic and care work to society and compensate them for it. Since then, many other States have followed suit. Among them are Karnataka, Maharashtra, and Jharkhand.

About 81.5% women take part in unpaid domestic work, compared with 27% men, in India, according to the Time Use Survey 2024 released in February. In a day, women spent, on an average, 289 minutes on unpaid domestic services for household members, while men spent 88 minutes. Women also spent 137 minutes a day caring for their household members, compared with 75 minutes for men.

Saving up

As the scheme nears its second anniversary, women across the State say that the modest sum has not only helped them buy household items but has also given them financial independence and enabled them to save for education, get increased access to healthcare, and start businesses. The scheme benefits more than 1.14 crore people. However, it is not without shortcomings: many women report that they have been left out of the scheme or have received benefits only sporadically in the last two years.

“This ₹1,000 might seem to be a very small amount, but it gives me the confidence that I can handle emergencies without borrowing. The monthly support isn’t just a financial benefit, it’s a source of dignity and independence,” says V. Malar, a domestic worker in Tiruchi.

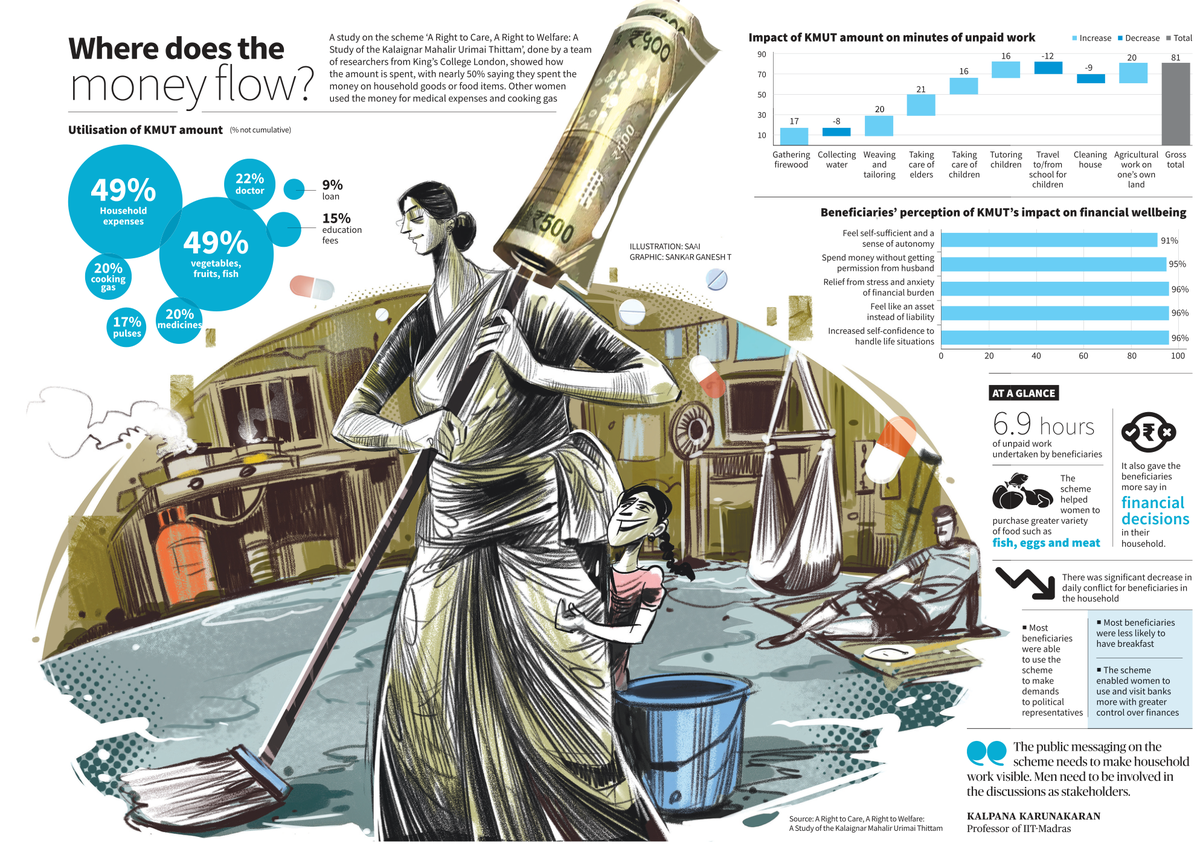

A recent study on the scheme, ‘A Right to Care, A Right to Welfare: A Study of the Kalaignar Mahalir Urimai Thittam’ — done by a team of researchers who are part of the Laws of Social Reproduction project, Dickson Poon School of Law, King’s College London — showed that 49% of the women spend the money on household items. The researchers were led by Prabha Kotiswaran, professor of law and social justice, Dickson Poon School of Law.

Pachayee, 60, of Pudur village in Erode, is a worker under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS). She says the aid enables her to buy essentials for which she earlier had to rely on her husband. She adds that along with the government’s free bus travel scheme, the monthly assistance has allowed her to save a small portion of her earnings, for the first time.

‘A safety net’

A. Pushpa, a domestic worker from Chennai, calls the aid a safety net. “By the 15th of every month, our salary would run out. We would be worried about how to pay for essential items like gas cylinder, which now costs almost ₹900. But, with this money, we are now able to manage the affairs with some ease,” she says.

A. Durga Devi, a single mother from Madurai, and A. Mariammal, 47, a farmworker from Thappathi village in Ettayapuram taluk of Thoothukudi, saved the money for their children’s education. Ms. Mariammal did not have a regular income for years until the sum under Kalaignar Magalir Urimai Thogai started reaching her bank account a few years ago. “I saved the amount for months, and with some additional money, I paid my son’s college fees.”

Ms. Mariammal notes that the amount has given women the hope that they can borrow from others in times of emergencies and repay the loans.

A common problem

The ability to repay debts is a common thread in the lives of women The Hindu spoke to across the Cauvery delta districts. “I have taken out five loans from different microfinance companies,” says Indira G., an agricultural worker of the Parasanallur panchayat in Mayiladuthurai. “For one of the loans, I pay ₹50 daily to an agent who comes to my home, for another, I pay ₹500 weekly, and for the rest, I pay ₹1,600 monthly. Agricultural work is available for only three months a year. For the rest of the time, we sit at home and the debts keep mounting.”

K. Manimala, 60, of Pallapatti in the Salem Corporation, says the money helped her travel in autorickshaws in times of emergencies. “It [₹1,000] may be nothing for the middle class or the rich. But, for women like me, it means independence. Earlier, if I wanted to give money to my grandchildren when they visited me, I had to ask my husband for it. Now, I am able to give them money.”

M. Eshwari, 38, of Tiruchi started a snacks shop with the money she received under the scheme. “Earlier, we used to depend entirely on my husband’s daily wages, which were uncertain. But, after receiving the ₹1,000, I saved a little every month. Eventually, I bought a gas stove, some utensils, and ingredients. It may seem insignificant, but for me, it’s a new beginning. I feel proud to earn on my own and contribute to my family.”

Hiccups

Many say that they have applied for the aid up to three times, but the money still hasn’t reached them. “There has been no SMS regarding the rejection of our applications. Just a message that I have registered [myself]. Nobody is telling me what went wrong,” points out A. Deepa, a domestic worker from Chennai. Some receive the money infrequently. “I applied when the scheme was announced. I did not get it for two months and then I got it for the next three months. It’s unpredictable…,” says B. Radhika, another domestic worker, who earns ₹6,000 a month.

Professor Kotiswaran says Tamil Nadu is one of the few States that makes a mention of unpaid domestic work in its notification. “It put the recognition on the table. However, there is a need for the scheme to go beyond recognising and reducing unpaid work too. Right now, caregivers are being punished.”

‘Due recognition needed’

Experts stress that through awareness programmes, educational instructions, or public advertisements, Tamil Nadu could educate the masses on its importance. “Tamil Nadu is in a vanguard position. Care work needs to be recognised, in all its forms, whether they are paid or unpaid. Whether it is done by Accredited Social Health Activists or Anganwadi workers or paid domestic workers, care work needs its due recognition in all policies and not just honorariums,” she adds. The report shows that given an option, women overwhelmingly prefer paid work. But it’s a double-edged sword, experts point out. “Even if we do reduce unpaid work and have decent work opportunities, employers are reluctant to hire women as they are looked up to execute their care responsibilities, taking care of sick parents and children, and they are most likely to end up taking time off work,” says Professor Kotiswaran.

‘Essential need’

Akshi Chawla, an independent researcher and writer, underscores the need to stop looking at care as something that only women should provide and look at it for what it is: an essential human need. “All human beings need care at some stage in their lives, whether it is in childhood or old age, or in times of ill-health or injury or disability. Instead of expecting women to shoulder all the care work, we need to design comprehensive policies and infrastructure that can help redistribute the care work, besides ensuring that all those who need care are able to access it easily. The state should ensure wider availability of safe and good quality care facilities [including crèches and elder-care facilities] that can be accessed by everyone who needs it,” she says.

A senior official in Tamil Nadu’s Special Implementation Programme Department says, “We want the scheme to help people as much as possible and alleviate poverty. However, we will look at the broader idea of care work. Through the camps under the Ungaludan Stalin scheme, we are addressing the issues of women who haven’t got the benefit. By mid-September, these problems would be resolved.”

‘Men must step in’

Noting that any kind of cash transfer scheme will benefit women, Kalpana Karunakaran, a professor of the Indian Institute of Technology-Madras, says, “It comes as a relief for women in the lowest of caste-class stratification. We must remember that the original concern was to monetise and make visible women’s unpaid care work. So, Kalaignar Magalir Urimai Thogai must not remain a poverty alleviation scheme. The public messaging on the scheme needs to make household work visible. Men need to be involved in the discussions as stakeholders. Why can’t influential men in power participate in media campaigns with the message that doing household work is everyone’s responsibility and not just women’s?”

(With inputs from Sibi Sreevathson T.C. in Coimbatore; S.P. Saravanan in Erode; M. Sabari in Salem; C. Palanivel Rajan in Madurai; Shankari Nivethitha B. in Kanniyakumari; and M. Nacchinarkkiniyan and Ancy Donal Madonna in Tiruchi)