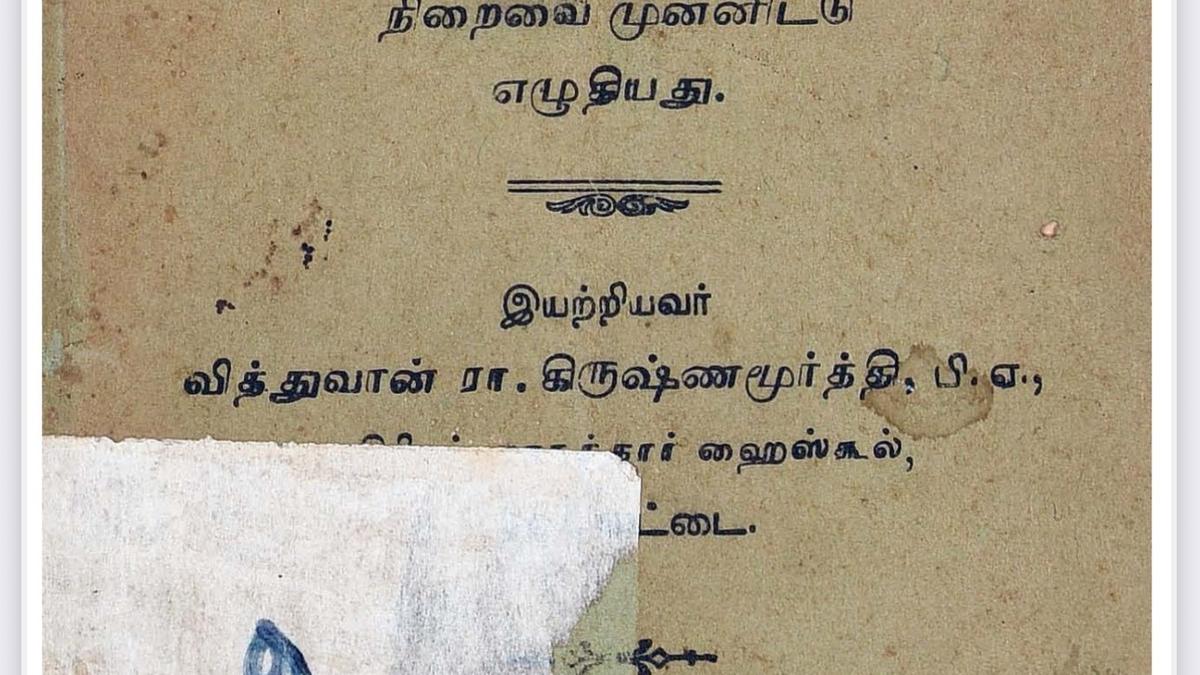

Chennai Kanchi, a poem on the city, was written in 1939 by Ra. Krishnamurthy, teacher at the Nagarathar High School, Devakottai

| Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

This is that month of the year when research and presentations on Madras reach fever pitch. Some, however, seem to be ever prepared with something new, or old, depending on how you look at it. Karthik Bhatt who is of that kind, sends me Chennai Kanchi, a poem on the city, written in 1939 by Ra. Krishnamurthy, teacher at the Nagarathar High School, Devakottai.

It was one of three publications on the city to be brought out that year, which some sections in the city observed as the tercentenary of its founding. The first was the Madras Tercentenary Volume, edited by Rao Bahadur C.S. Srinivasachari and containing articles contributed by various members of a tercentenary committee. The second was The History of the City of Madras written by C.S. Srinivasachari, and the third was Chennai Kanchi.

Given that Srinivasachari was himself with the Annamalai University as history professor, it is clear he must have known of Ra. Krishnamurthy’s skills as a poet and invited him to write. The work is based largely on the format of the famed Madurai Kanchi, a Sangam-era work that is part of the Pattupaatu compilation. Kanchi incidentally, does not refer to the temple town but is a form of verse. In his introduction to Chennai Kanchi, R.C. Subramania Iyer, lecturer at the Sri Meenakshi Oriental Training College, Chidambaram, which a decade earlier had been the seed of Annamalai University, offers some details on Kanchi as a format.

He writes of it as a long form of poetry where the impermanence of youth, wealth, etc. are contrasted with lasting glory by way of valour and salvation. The Chennai Kanchi while speaking of the glories of Madras, also warns the then ruling dispensation of the evanescence of rule, empire and domination. Even its lines at the beginning, ostensibly paying obeisance to King George VI are tongue-in-cheek – “O those who rule over this glorious land in the name of George VI who is king of a small country several thousand miles away.”

The work then goes on to describe Madras. It begins with the arrival of Francis Day, the growth of the Fort, the foundation of Black Town, its demolition after the French leave and then the construction of New Black Town. It then proceeds with the development of company village such as Chintadripet, Washermanpet, and Colletpet. It dwells on the manner in which the Nawab was made to give up his lands and how the areas of Thiruvallikeni, Nungambakkam, etc., gradually became part of Madras. Interestingly, it says Francis Day arrived in Mylapore!

There follows a description of various important locations of the city – the beach, the University buildings, Ice House, the Senate House, and Queen Mary’s College. Likewise the Harbour, George Town, the High Court campus, Central Station, Général Hospital, the Madras Medical College, the Zoo, and the old jail are all mentioned. At that time, the wireless was clearly a wonder and the poem describes in detail its use by the police around Fort St. George. What is of interest is the complaint about motor car proliferation and the noise consequently caused. It makes you wonder as to what the composer would have thought of the situation today.

The work ends with the poet telling the British to leave this city to Indians and let them get on with it. And then comes the sting – which is on the back cover – copies of the book can be had from an address at Basavangudi, Bangalore. Surprising that nobody in Madras city could take on the task of selling a book on Madras!

Published – August 20, 2025 06:30 am IST