Basharat Peer was in Delhi on the evening of March 24, 2020, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressed the country on television and announced a countrywide, complete lockdown. “Four hours later, nobody would be allowed to step outside his or her home,” Peer writes in an e-mail conversation, reliving the urgency of the period. At the time, Peer was working as an International Opinion Editor for The New York Times. The COVID-19 pandemic was the most significant global story, and he was commissioning and editing essays about it from Asia, the Middle East, and Africa—the regions he was responsible for.

One day in mid-May, he came across a grainy photograph on Twitter (now X) of Mohammad Saiyub, a Muslim, and Amrit Kumar, a Hindu, sitting on a patch of burned earth by the side of a highway in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. “In the punishing May heat, Saiyub cradled Amrit, his friend, who had collapsed from heatstroke. They were trying to reach their village in Basti district of Uttar Pradesh, which was around 1500 kilometres from Surat in Gujarat, where they worked in textile factories,” says Peer.

This was the time, he remembers, when the factories and businesses shuttered, millions of workers who had left their villages in “de-industrialised northern and central India for cities in the industrialised western, and increasingly, southern India” started running out of food and money. It was also a time when, he underlines, for several weeks, news channels and social media networks were “flooded with the hashtag, #CoronaJihad.” “The utter disregard for the lives of the poor increased the feeling of despondency,” notes Peer.

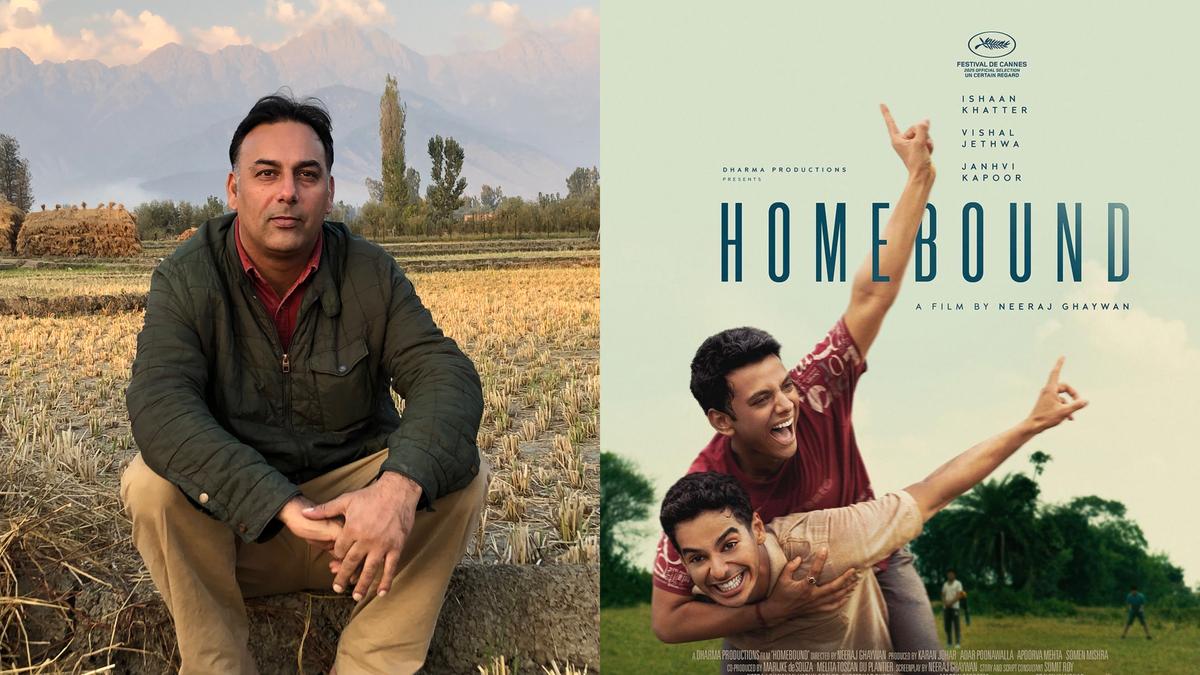

Basharat Peer with Md Saiyub

| Photo Credit:

Vivek Singh

In this backdrop, when he followed the story behind the photograph, the bond between Saiyub and Amrit emerged as a symbol of hope amidst the socio-political fault lines that the deadly virus exposed. This past week, the poignant story found screen life as Neeraj Ghaywan’s Homebound was showcased at Cannes, tearing up a global audience.

Peer is not new to this cross-breeding of fact and fiction. A decade ago, his much-acclaimed memoir, Curfewed Night, which chronicles the alienation of the youth of Kashmir, took the shape of Haider under the direction of Vishal Bhardwaj.

More than a year after the story of Saiyub and Amrit was published in the newspaper, Peer was in Mumbai and met Somen Mishra, a journalist who veered towards films and now heads creative development at Dharma Productions. “I introduced him and his colleagues to The NYT people, and Dharma bought the rights. Somen told me he would bring Neeraj Ghaywan on board to direct the film. I met Neeraj, and we had a lengthy conversation. I was quite certain he had the right sensibility and would adapt it beautifully. And he did.”

Excerpts from an interview:

Why did you decide to follow the story behind the photograph?

BP: I kept returning to the grainy photograph by an unidentified person. The friendship, the compassion, and the trust it captured moved me immensely. It was an embodiment of fundamental human decency. I called my editor in New York and told him, ‘I have to write about it myself.’ I am diabetic, had high blood pressure at the time, and was at somewhat greater risk, but that image didn’t leave me. In a world filled with hatred and callousness, that image of Mohammad Saiyub and Amrit Kumar felt like the rain of mercy from the heavens. I had to know more about their lives and journeys. I had to do it myself, for myself.

Apart from their friendship, did Saiyub and Amrit’s social and cultural identities prove to be the defining factors?

BP: Their identities definitely added important layers to the story, gave greater meaning to their everyday struggles, and their immense hard work in building a better life for themselves and their families. That particular moment was difficult for every worker, but the loss of livelihood and opportunity exacts a greater price on people from the most marginalised and the most besieged communities. My awareness of that made every victory of theirs—Amrit buying his first pair of jeans, a cell phone, and eventually helping his parents build a small brick house —really important for me. And I wrote of them as heroes with agency.

The headline “Taking Amrit Home” has a deeper, divine meaning. How did it come about?

BP: The headline came from a conversation with a colleague. She has great literary sensibility, and when she suggested we use it as the print headline in the Sunday edition of the paper, I immediately agreed. To me, it embodied Saiyub’s character, his friendship, and his love for his friend. He was not going to let Amrit be cremated as an unknown body in the middle of nowhere. He ensured that he took Amrit’s body home, and they buried him properly in a Dalit graveyard outside their village, in a field of lush grass and mahua trees.

From migration and health infrastructure to social divide and communal polarisation, the story brought out the fault lines that exist in Indian society. It still left the reader, particularly those who understand the subcontinent, with a sense that there is hope.

BP: A lot of people in the middle and upper-middle classes closed their hearts and doors on people who weren’t from their religious groups in the past decade. Even highly educated people who wield positions of importance in our cultural worlds, in the media, in the think tanks, in academia, and films. Even people I used to call friends once. Saiyub and Amrit gave me hope. They faced much greater difficulties, yet they did not give up on human decency, friendship, or being there for one another.

Is a feature film a better medium to take a story to a larger/ varied audience?

BP: I don’t think films are a better medium than essays or books. Films are simply different. They appeal viscerally to our senses; they can be more popular. However, the complexity an essay or a book can bring to the world, apart from its emotional import, is much greater. The influence the written word has on the world is immensely greater and more serious than cinema can ever have.

I love cinema and have recently completed a new screenplay, but most films can’t do what a proper essay can do. Essays like A Modest Proposal by Jonathan Swift, James Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son, and George Orwell’s Shooting an Elephant are essays that you return to year after year. In the contemporary Indian public discourse, the essays of Ashis Nandy, Pratap Bhanu Mehta, and Pankaj Mishra are worth the universe. They have shaped the taste, the politics, and the sensibility of millions in a fundamental way. In the past 19 months of Israel’s genocidal violence on Gaza, millions of videos have filled the public sphere. Still, nothing I have seen matches the intelligence and the power of the essays by Palestinian writers Isabella Hammad, Mary Turfah, or Mosab Abu Taha. You can distill and illuminate decades and worlds in an essay. All you need is a pen and a notebook.

Tell us about the physical experience of traveling to Devari and meeting Saiyub and his family at the height of the pandemic

BP: I drove with a photojournalist colleague to Devari from Delhi. We had the shields, masks, and hand sanitisers, and we were quite careful. But when we reached the village, nobody was wearing a mask. Amrit’s family had lost a son, Saiyub had lost his friend, and I simply couldn’t sit them with my shields and masks. I left it all in the car and had chai with them, and we talked. The protective gear would have become a wall of privilege between them and me. I got rid of it, and we talked; I’m glad I did. I was able to write everything. I didn’t leave anything out.

Are you in touch with Saiyub?

BP: Saiyub and I speak every few months. We send each other voice notes. He is a lovely, hardworking young man. He eventually left the village, drove a truck, worked in Mumbai for a bit, and has been working in Dubai for the past few years. Initially, he was quite homesick, and working in construction in Dubai is quite tough, but he seems better adjusted there now. I can’t wait to watch Homebound with its hero, Saiyub, whose character is played by Ishaan Khattar.

How is the adaptation of Taking Amrit Home different from Curfewed Night?

BP: Homebound and Haider are very different in style and treatment, though both films deal with urgent and important political questions and complex realities. Additionally, with Haider, I adapted Hamlet, reimagining it for the Kashmir of the mid-1990s, and wrote the screenplay alongside Vishal Bhardwaj. In Homebound, Neeraj and his team of writers adapted my story.

Published – May 28, 2025 01:34 pm IST