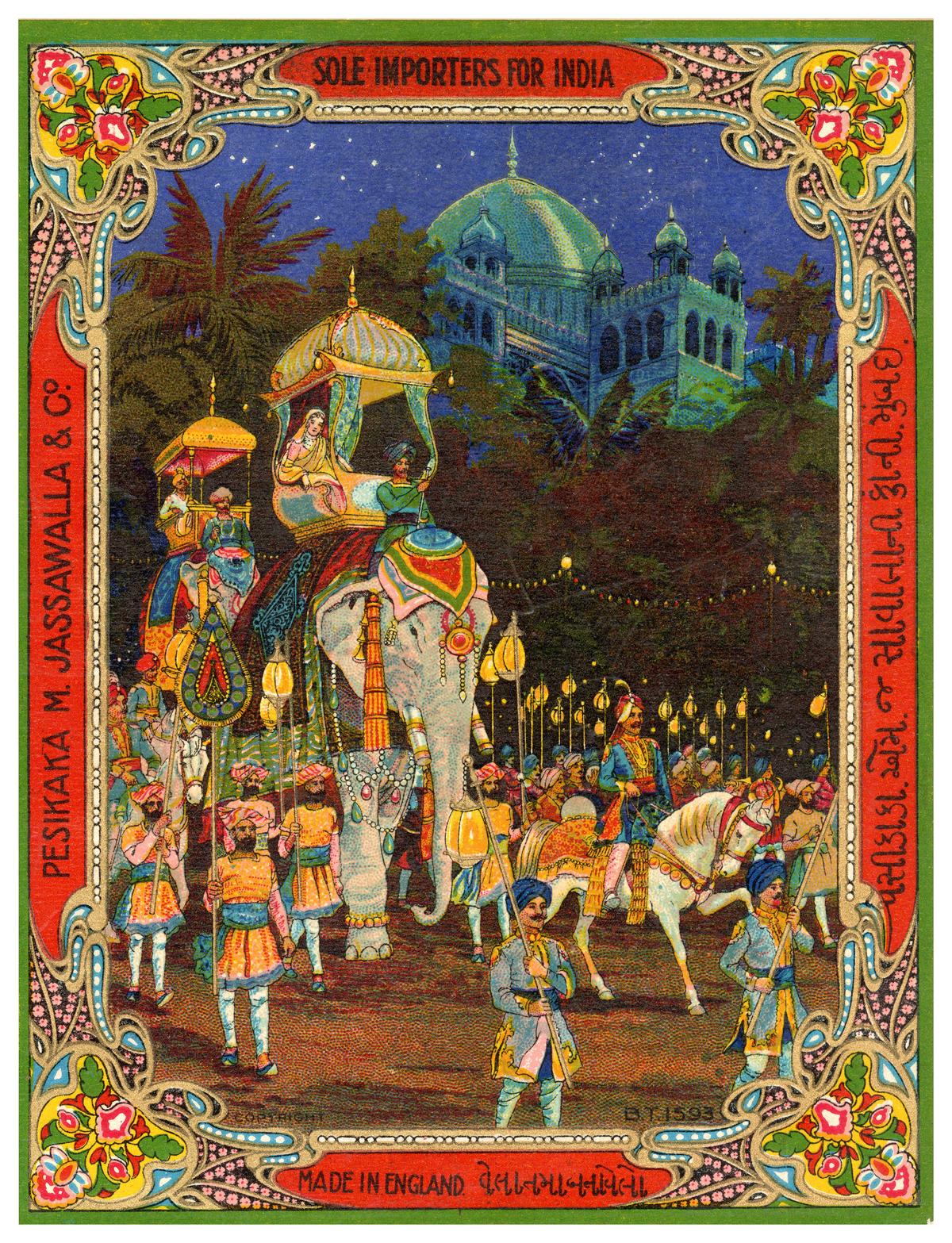

Images of women in traditional attire, dancing elephants and portraits of maharajas make for artistic visuals

| Photo Credit: Courtesy: MAP, Bengaluru

During the Indo-British textile trade, between the late 19th and mid-20th centuries, a few unique textile labels emerged. They were were known as tikats, tikas or chaaps. They were not simple tags attached to fabric, they carried imaginative and colourful visuals. Today, these textile labels are being seen as cultural and historical markers.

Four hundred such labels are on display at ‘Ticket Tika Chaap, The Art of the Trademark in Indo-British Textile Trade’, an ongoing (till November) exhibition at Museum of Art And Photography (MAP) in Bengaluru. Curated by Shrey Maurya, research director-MAP Academy and Nathaniel Gaskell, author, editor and co-founder-MAP, the exhibition features labels, correspondences between merchants and trademarking officers in England, stamp markings that were applied on bales of clothes and a few photographs.

MAP has a collection of 7,000 textile labels and Shrey and Gaskell took up the subject as an yearly curatorial project. “Popular art is something we wanted to look at this year. It took us close to two years to put the exhibition together. A year-and-a-half was largely spent on researching and looking at images,” shares Shrey.

The images on the labels are representative of their times

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy: MAP, Bengaluru

The labels carry diverse visuals — dancing elephants, portraits of maharajas, deities, women in traditional attire, symbols of industrialisation such as fans, telephones and buses, British imperialistic symbols, religious iconography and photographs of Indian merchants. All tickets have a well-defined margin with names of the business printed on them in English and regional languages.

The curators went through 7,000 images and categorised them into subject-based groups. “It was exhausting but it opened up a whole new world. The visuals on the labels had a meaning and seemed to hold within them several untold stories from the past. The creativity that had gone into making them led us to the history of branding and advertisement,” says Shrey.

She adds not much has been written about textile labels in the art-historical context except for a few by the likes of Jyotindra Jain, Kajri Jain and the Tasveer Ghar Project.

While putting together the exhibition, the curators constantly thought about the people and processes behind the creation of these labels. “It was truly intriguing. Not just the trademarking process and printing, we wondered how they came up with the idea of images on labels and who would have drawn them. There is no record of the artists.”

Shrey shares that the images are representative of their times. “Tickets are reflective of society, culture, rituals, lifestyle and choices of people then. Also, the print revolution brought about an explosion in imagery as seen on these labels.”

The tickets were designed and printed in England and attached to fabrics sold directly by major British cotton mills such as Graham Co., Manchester or a few Indian merchants, who bought clothes from them and sold them under their name.

The exhibition also has on display the correspondence between a Gujarat-based trader and the printing establishment in Britain. The trader’s letter says: “This is the design I want; please make it and send it to me”. “Most merchants based in India were writing to printers in Manchester to create labels for them,” says Shrey.

The registering and trademarking process was a time-consuming one and happened through letters and telegraphs. “There was a risk of rejection. The trademark office’s role was to make sure that the designs were different to avoid fight among merchants claiming that someone was trying to sell goods under their name.”

400 tickets are on display

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy: MAP, Bengaluru

Shedding more light on the process, Shrey points out the fine network among people involved in the creation of tickets. She cites the example of the correspondence between a Gujarati merchant and a trademarking officer. “Since the trader had mentioned the design specifications in Gujarati, the printer sends the letter to an expert in Oriental languages for translation.”

Maurya also highlights a ticket that is an exact copy of an artwork done by the American artist, Maxwell Parrish in 1909 called ‘The Lantern Bearers’. “Somehow that image makes its way to England, where an artist takes the drawing and replaces the figures in them with saree-clad women for Indian customers. Despite lack of technology, it’s interesting to note that these people were not working in a vacuum, there was enough interaction and exchange happening,” says Shrey.

(The exhibition is on at MAP, 22, Kasturba Road, Bengaluru, till November 2025.)

Published – May 27, 2025 05:11 pm IST